|

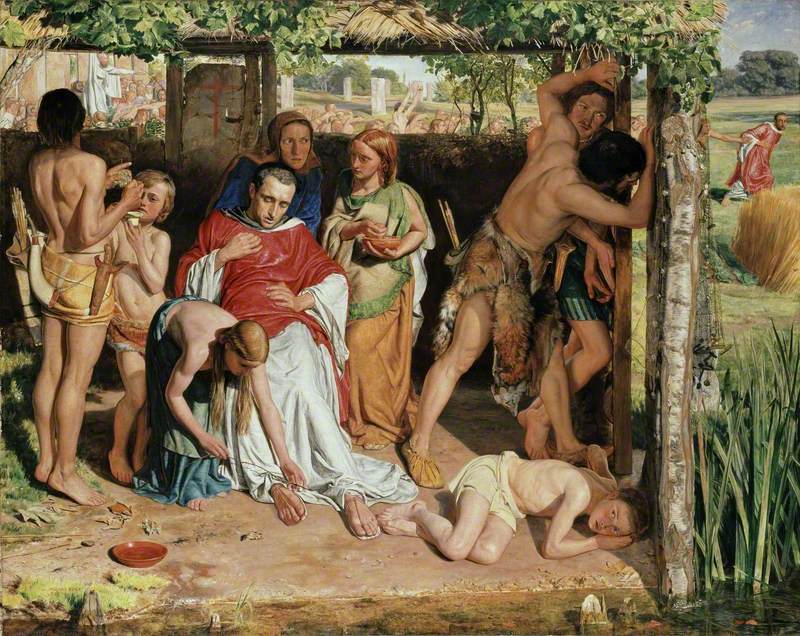

| Manuel Joaquim de Melo Corte Real, Nóbrega e seus companheiros (Nóbrega and his companions), 1843, oil on canvas, 222.5 x 323.2 cm, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Source. |

Today, Corte Real's painting is troubling in its depiction of a 'savage' indigenous tribe. After first landing in Brazil (as the territory would later be named) in 1500, Portuguese colonisers discovered that the natives practised anthropophagy (cannibalism) – an indication of their perceived immorality which must be swiftly stamped out through diligent missionary work. Indigenous peoples came to be defined by their anthropophagy, and were typically depicted as bestial subhumans who needed to be 'civilised' by their European conquerors.

|

| Padre António Vieria (1608-97) 'preaching' to indigenous men. Source. |

Catechism and civilisation were central to the whole colonial project [...] [The Jesuits] were eventually called 'the soldiers of Christ', and that is how they ended up, a veritable army of cassock-clad priests, fighting the Devil and at the ready to save souls [...] Missionary work in Brazil was seen as dangerous – after all Pedro Correia had been devoured by the Carijó Indians in 1554, and Dom Pedro Fernandes Sardinha [...] had been eaten alive by the Caeté Indians in 1556 [...] The best thing to do was to indoctrinate these people, who, unlike the natives of the East, 'lacked any faith or religion'.[1]When Corte Real's painting was exhibited in 1843, it was accompanied in the catalogue with a description of the incident which the artist had depicted:

The historian of the Jesuits in Brazil reports that, wanting these missionaries to destroy the nefarious custom of anthropophagy [cannibalism] among the Gentiles, they dared to take from the hands of women, and from the stove already lit, the corpse of an Indian they were preparing to be devoured; the savages hesitated for a moment by such boldness; but soon afterwards they went to pursue the priests, forcing them to retreat to the village of São Salvador da Bahia; and it narrowly escaped being plundered on that occasion by a few thousand of these enraged cannibals.[2]All this I learned later (and am still learning, as Brazil's history is long and complex). My immediate reaction to Nóbrega and his companions when I saw it in Rio was that it reminded me of a British Pre-Raphaelite painting that I know very well: William Holman Hunt's Converted British family:

|

| William Holman Hunt, A converted British family sheltering a Christian missionary from the persecution of the Druids, 1849-50, oil on canvas, 111 x 141 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Source: Art UK. |

|

| Detail of Hunt's Converted British family. Source. |

Yet are there similar forces at work here, at least thematically?

One similarity is the way in which both artists chose to depict the central male figures who are being rescued from the 'barbarous natives'. Scholars have already highlighted the complex Christian iconography displayed throughout Hunt's British family. The rescued missionary, clad in red and white, slumps lifelessly in the arms of the elder woman, dressed in Marian blue. Their poses easily evoke the pietà motif – Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus – popular in religious art:

|

| Detail of Hunt's Converted British family |

|

| Gerard David, Lamentation, ca. 1515-23, oil on oak, 63 x 62.1 cm, National Gallery, London. Source. |

|

| Detail of Corte Real's Nóbrega and his companions |

|

| Raphael, The deposition (The entombment), 1507, oil on wood, 184 x 176 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome. Source. |

Comparisons between Corte Real and Holman Hunt are not perfect. There are the stylistic and technical variances already mentioned – Hunt's Pre-Raphaelitism versus the academicism of Corte Real's picture. The racial differences between the Christians and 'savages' are far more pronounced, and more problematic, in Corte Real's painting, which has its roots in Brazil's colonial past. Indigenous people were slaughtered or exploited for labour by the Portuguese settlers in the sixteenth century – horrors which we are reminded of more easily when looking at Corte Real's painting than when we look at Hunt's picture. Admittedly, I do not know nearly enough about the spreading of early Christianity in Britain – whether this spread was relatively peaceful, or if it ever reached the same level of appalling violence as when the Portuguese colonised Brazil (this does seem unlikely).

|

| William Holman Hunt, Study for the head of the missionary in 'A converted British family', ca. 1849, reproduced in Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1905), vol. 1, p. 195 |

This is all part of a much larger issue than this simple blog post can deal with – indeed, I was somewhat cautious in posting it as it touches on racial and religious issues which I somehow don't feel qualified to comment upon. Still, I hope to have shown that Brazilian art, unfamiliar as it is to most non-Brazilian viewers – is as potent and complex as the British pictures which we're so accustomed to studying. Comparing Hunt's Converted British family with Corte Real's Nóbrega has given me a new perspective on the former, and raises questions of race, religion and empire. It may be a superficial comparison, but it's compelling and may warrant further consideration. I hope to continue these kinds of comparisons in future posts.

Notes

[1] Lilia M. Schwarcz and Heloisa M. Starling, Brazil: A Biography, English edition (London: Penguin, 2018), pp. 26-27.

[2] Quoted in Yobenj Aucardo Chicangana-Bayona, 'Presença do passado no Brasil imperial: a tela Nóbrega e seus companheiros (1843)', Varia Historia, vol. 27, no. 45 (Jan./June 2011) – translated from the original Portuguese using Google Translate.

[3] William Michael Rossetti used the term 'savage' in relation to the Celts in Hunt's painting in his diary on 6 March 1850: '[Hunt] has done the priest's drapery, put in the other priest outside [...] painted [F. G. Stephens's] head for a savage outside, with various others'; William E. Fredeman, ed., The PRB Journal: William Michael Rossetti's Diary of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 1849-1853 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), p. 61.

[4] The term 'Indian', while it may sound offensive to European readers, is still used by many Brazilians today to describe indigenous people in Brazil (including in Schwarcz and Starling's book Brazil cited above). However, some indigenous groups in Brazil have been promoting the term 'indígena' as a better alternative, and I have used it here.

[5] Fredeman, PRB Journal, p. 4 (19 May 1849).

No comments:

Post a Comment