Note: I'm not sure if the comparisons in this post have been made by Leighton scholars before – if they have, my apologies for the oversight!

During a visit to

Leighton House Museum in the New Year, I saw this painting by Frederic Leighton (1830-96), entitled

Rustic music:

|

| Frederic Leighton, Rustic music, 1861, oil on canvas, 109 x 91 cm, Leighton House Museum, London. Source. |

The sitter is John Hanson Walker (1844-1933). Walker was discovered by Leighton while he was working in his father's curiosity shop in Bath in the late 1850s. Leighton was struck by his beauty and chose him as a model. (This incident is eerily similar to the legend/fable/myth of Elizabeth Siddall being discovered by Walter Howell Deverell while she was working in a London hat shop.) In 1861 Leighton wrote to his sister: 'I have just returned from a fortnight in Bath, where I have finished the two Johnnies, I believe, and hope you will like them'.

[1] The 'two Johnnies' refers to two paintings for which Walker had modelled: one was

Rustic music, the other was entitled

Duet. Leighton submitted both pictures to the 1862 Royal Academy exhibition, but only

Duet was accepted.

|

| Frederic Leighton, Duet, 1861, oil on canvas, 61.2 x 44.7 cm, Royal Collection Trust, London. Source. The painting was given as a birthday gift to Queen Victoria by the Prince of Wales in 1868. |

Rustic music and

Duet, painted simultaneously, depict near-identical subjects: a youth in an outdoor pastoral setting, wearing the same rustic outfit and holding the same metal flute in both pictures. They contain a suggestion of music – an interest among artists in the 1860s – and seem designed to emphasise the youth's good looks: his full red lips, tousled hair, flushed cheeks and thoughtful eyes. (Walker was around 17 years old when these paintings were made.) Plenty of scholars have speculated that Leighton had homosexual tendencies, although this is difficult to confirm through documentary evidence as he left no diaries behind and he was generally evasive about his personal life.

[2] Certainly, he appreciated Walker's beauty enough to paint him, and he subsequently took on the young man as a pupil and studio assistant. We could even describe Walker as Leighton's 'muse' – a role typically assigned to women in heteronormative accounts of nineteenth-century art.

While

Duet adopts a different compositional format, it doesn't take much effort to see in

Rustic music a clear analogy to Dante Gabriel Rossetti's

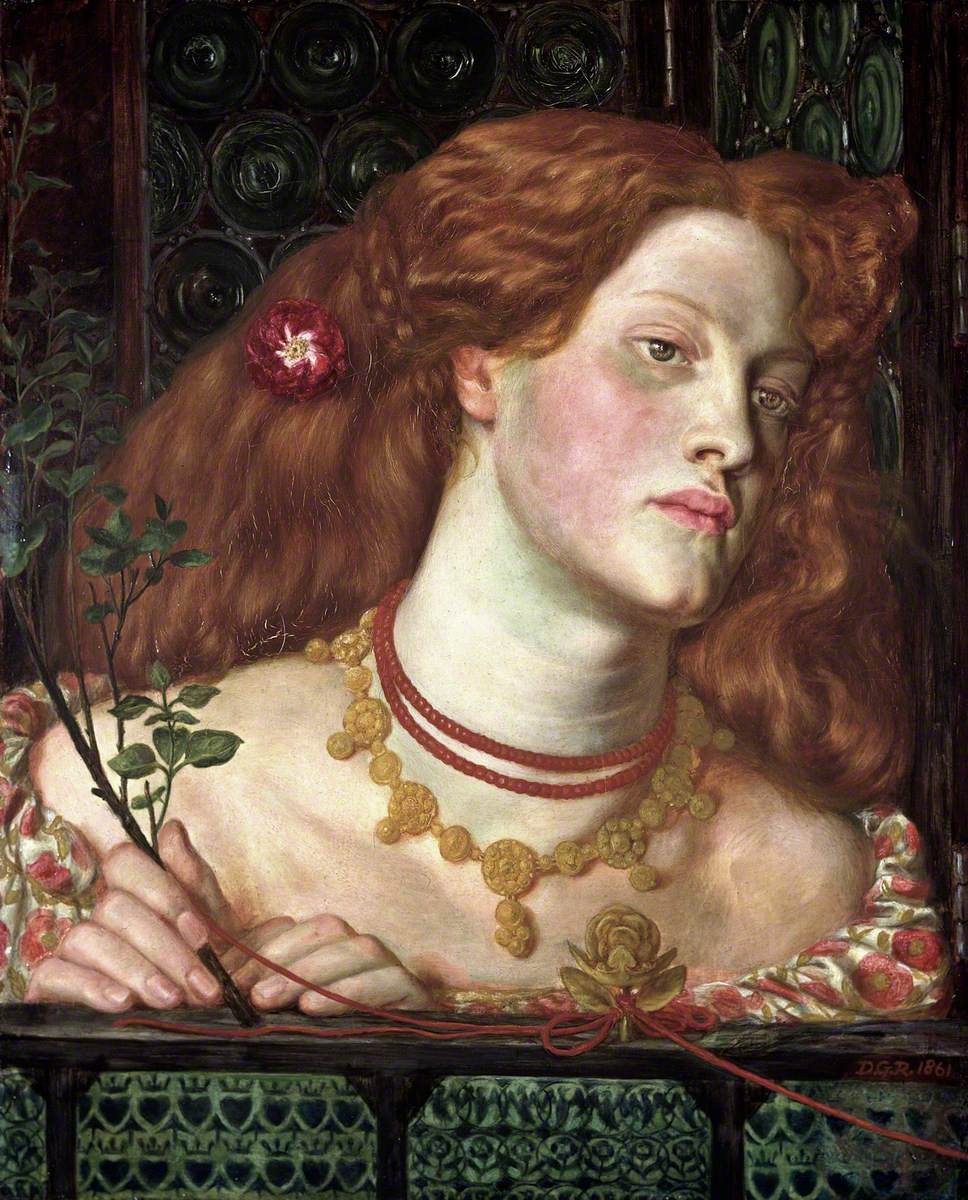

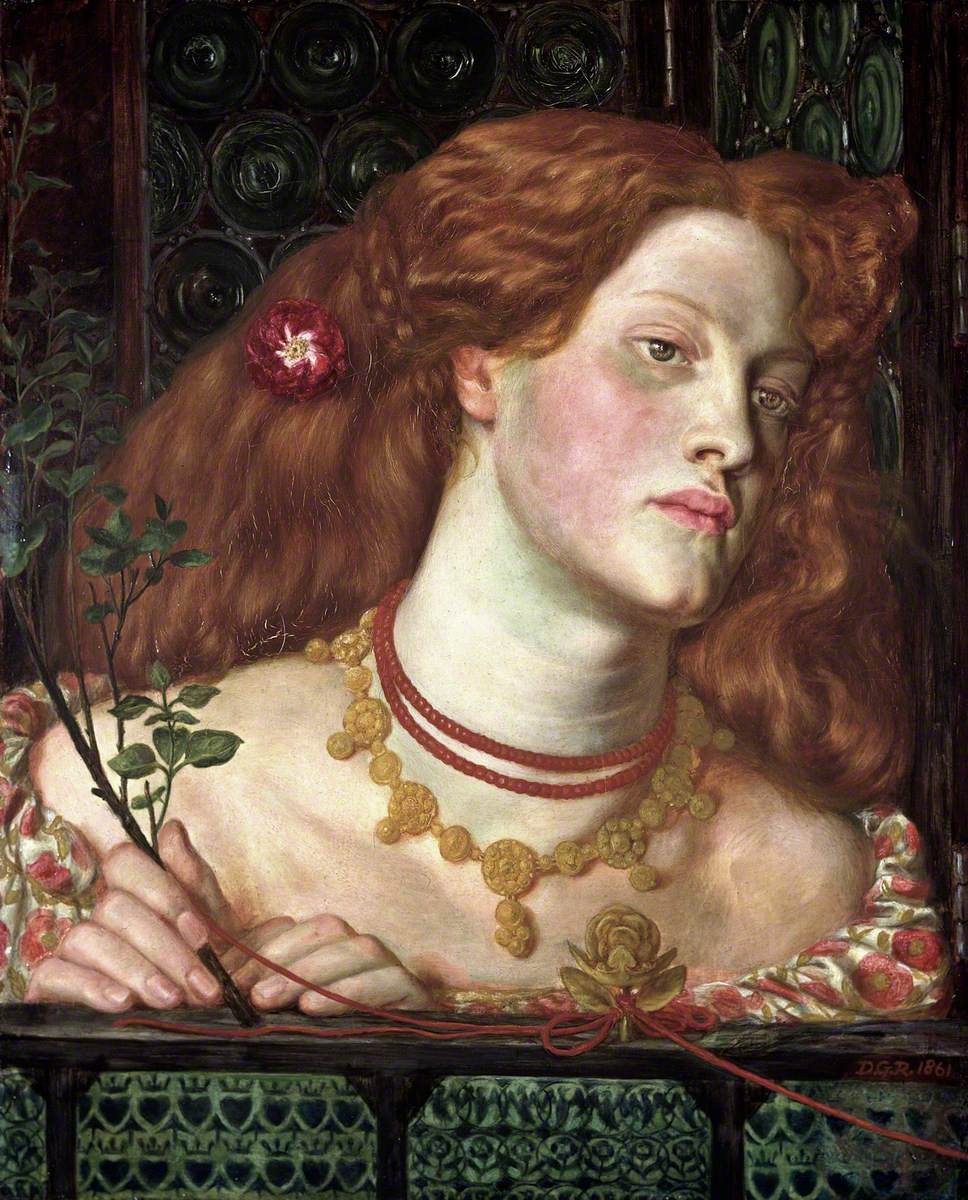

Bocca baciata, painted around two years earlier in 1859:

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Bocca baciata, 1859, oil on panel, 32.1 x 27 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Source. The model was Fanny Cornforth, one of the most recognisable Pre-Raphaelite models. |

Rossetti exhibited this small picture at the private Hogarth Club, of which Leighton was a member, in 1860 – there is no doubt that he would have seen it.

Bocca baciata was the first of many images by Rossetti presenting a single female figure in a bust format with a ledge in the foreground and a compressed background containing flowers or other decorative elements. These are the images for which Rossetti is best remembered, and which have become synonymous with the term 'Pre-Raphaelite' for many viewers.

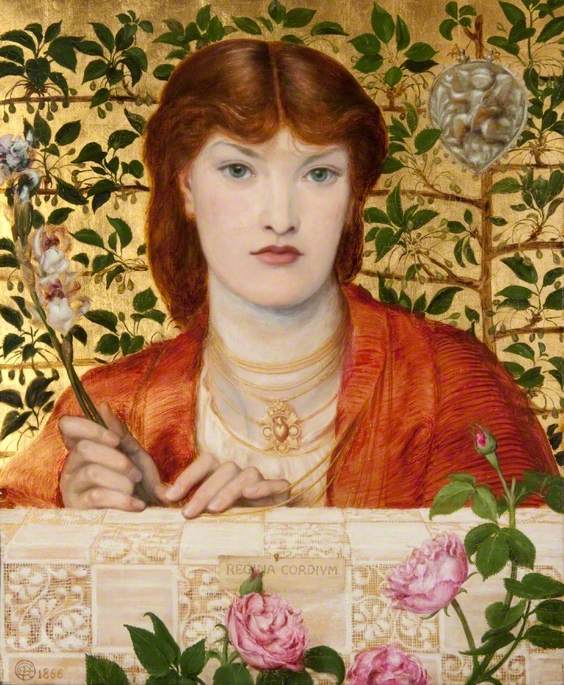

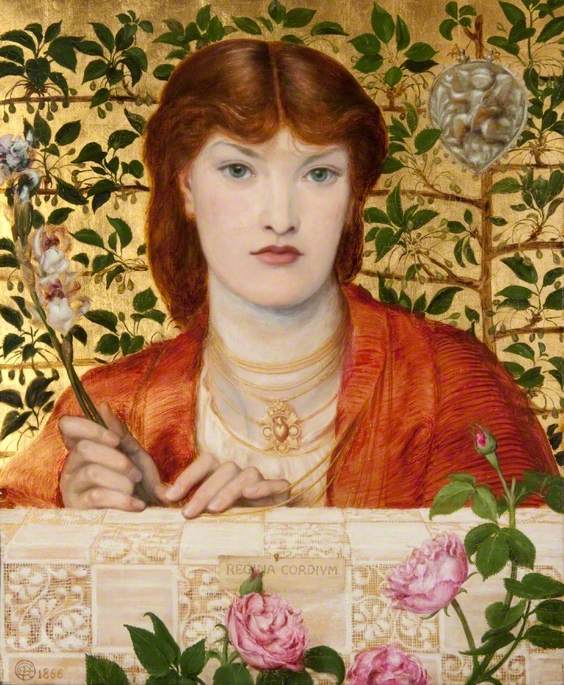

Fair Rosamund, painted in mid-1861, several months before Leighton's

Rustic music, continues the device:

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Fair Rosamund, 1861, oil on canvas, 51.9 x 41.7 cm, National Museum Wales, Cardiff. Source. |

Leighton has clearly borrowed Rossetti's pictorial strategy of portraying women for his own painting of a male youth whom he considered beautiful. Rustic music has a shallow ledge in the foreground on which the boy's hands rest. The torso and head are viewed frontally and fill most of the space, with the head cocked slightly to the viewer's left (as in Bocca baciata), and the human figure is surrounded with natural objects – thistles and trees in this case. There is an additional similarity in Leighton's brushwork, which has a soft, luminous quality as in Rossetti's paintings at this time. (Rossetti acknowledged Venetian painting as an influence on Bocca baciata.) Rossetti's women are invariably shown clutching an object which accentuates their slender fingers placed on the shelf before them; the same quality is apparent in the boy's fingers grasping the flute, which have a delicate, dextrous appearance. Like Rossetti, Leighton has used highlights on the fingernails and knuckles to call attention to the boy's preparation to play music.

The suggestion of music in Leighton's picture finds its equivalent in Rossetti's painting made four years later,

The blue bower, in which Fanny Cornforth's fingers are about to pluck the strings of her instrument – just as we might imagine the notes which will emerge from the boy's fingers once he raises the flute to his lips.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The blue bower, 1865, oil on canvas, 84 x 70.9 cm, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham. Source. |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Regina cordium, 1866, oil on canvas on panel, 59.7 x 49.5 cm, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow. Source. Another interesting point of comparison with Leighton's Rustic music. |

Now, what can we take from this?

We must take care when reading the work of a deceased artist whose sexuality we cannot easily define. Leighton may simply have found this type of composition visually appealing, or he could see how popular (saleable) Rossetti's work in that line was becoming. The fact that Leighton was exploring the idea of transposing a male figure into a typically Rossettian pictorial space, where we would ordinarily expect to see a woman, is insightful in itself.

Rustic music is not as clear in its intentions as, say, the work of Simeon Solomon produced contemporaneously in the 1860s, such as the now-famous

Bacchus of 1867:

|

| Simeon Solomon, Bacchus, 1867, oil on paper laid on canvas, 50.3 x 37.5 cm, Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery. Image: Birmingham Museums Trust. |

Solomon, of course, was persecuted for his homosexuality in 1873, and his works can be more easily read as gay or queer in nature (several, including

Baccus, were included in the exhibition

Queer British Art at Tate Britain in 2017). Scholars have evidently had more difficulty with Leighton.

Perhaps I'm being too coy. It can be argued that Leighton was examining male beauty in much the same way as Solomon in his

Rustic music. That the model, John Walker, was only 17 when it was painted – and he was still a boy when Leighton discovered him – is something we might also take with caution, although there is no evidence to suggest that anything sinister 'went on'. Walker seems not to have minded the older man's attentions, while Leighton supported Walker's burgeoning talents as an artist and painted a fine portrait of Walker's eventual wife in 1867:

|

| Frederic Leighton, Mrs Frances (Nan) Hanson Walker (née Whitaker), 1867, oil on canvas, 46.4 x 41.3 cm, Tate, London. Source. Many thanks to Barbara Bryant for informing me of 'Nan's' proper name! |

Given Leighton's central position in the British art world in the 1860s, and his acquaintance with avant-garde theories, it's also reasonable to see

Rustic music simply as an expression of the developing Aesthetic Movement, with its lack of narrative and emphasis on music/sound. Earlier in 1861, Leighton exhibited at the Royal Academy his

'Lieder ohne worte' ('Songs without words'), a large, enigmatic painting inspired by Mendelssohn's cycle of piano pieces of the same title:

|

| Frederic Leighton, 'Lieder ohne worte', exhibited 1861, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 62.9 cm, Tate, London. Source. |

Hang on, haven't we seen the woman's face somewhere before? In fact, it's that of young Walker – a male figure modelling for a female one. If that isn't queer, I don't know what is.

I don't have any definite conclusions for this post, which arose out of my initial observations after seeing Leighton's

Rustic music. But it gets us thinking about male beauty as depicted by men in the mid-Victorian period – a topic which has received relatively little attention in studies of British art. It's a subject I would like to examine more in my research, so this post seemed a good place to begin.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Mrs Russell Barrington [Emilie Isabel Barrington],

The Life, Letters and Work of Frederic Leighton (London: George Allen, 1906), vol. 2, p. 85. The letter was probably written in December 1861, owing to a reference to Prince Albert's recent death (on 14 December).

[2] See Richard Norton, '

Fay and Babbo: The Gay Love Letters of Henry Greville to Frederic, Lord Leighton' (2014) for a discussion of this subject.

Hello Robert Somewhat belatedly I've read your new blog and thought you might like to know that John Hanson Walker's wife did have a name (though the Tate website does not show it). The Ormonds recorded her in their book as Nan (Frances) Whitaker. She was always called Nan. And, as it is known that Leighton's portrait of 1867 was a wedding present, it could be entitled Mrs Nan Hanson Walker or perhaps, more formally, as Mrs Frances (Nan) Hanson Walker or indeed without the Mrs. at all. I agree that the name of a female sitter should not be dependent on her husband's name and should, at the very least, give her Christian name in the title. Some might prefer to go by the title the portrait had at its first exhibition but that's another discussion!

ReplyDelete