|

| Me with Pedro Américo's vast canvas The battle of Avaí (1872-9) in the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 10 May 2018 |

How do you begin to study or engage with historical Brazilian art outside Brazil, particularly when you are based in the UK? Immediately there are some problems.

Firstly, there have been very few books on Brazilian art written in English – especially art from the nineteenth century, the period I'm principally interested in. Plenty of books have been published in Brazil, but this requires a working knowledge of Portuguese (which I don't yet have) and access to a library which contains these books in the first place.

Secondly, there are very few examples of Brazilian art in museum collections outside Brazil – at least in the UK. A search of the Art UK website reveals a dearth of Brazilian artists. Certainly, there were artists who travelled from Europe to Brazil in order to document (and to idealise) the 'New World' and its landscapes and peoples: notable examples include the Dutch painter Frans Post (1612-80) and the British artist and biologist Marianne North (1830-90). Works by these artists are available in London museums, such as this

Brazilian scene by Post:

|

| Frans Post, Brazilian scene, ca.1665, oil on 48.7 x 64.7 cm, Guildhall Art Gallery, London |

Or this vivid study of Brazilian flowers by North:

|

| Marianne North, Brazilian wild flowers, ca.1873, oil on board, 51 x 29 cm, Marianne North Gallery, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |

This leads to the third, historical factor: in the same way that few British artists went to Brazil in the nineteenth century, few Brazilian artists came here, that I'm aware of. Virtually no art by Brazilians was produced in the UK, so it was not commissioned or collected (do let me know of any examples of this).

Fourth, Brazilian art is absent from many art history curriculums in schools and universities, leading to a lack of awareness even among academics. I was lucky enough to attend one of the few state sixth-form colleges which taught art history at A level (Truro College in Cornwall if you're interested). Our textbook was E. H. Gombrich's

The Story of Art, which excludes Brazil from its 'survey of the history of art from the ancient world to the modern era'. This carried over into my undergraduate degree, which focused primarily on European painting and sculpture. My view of art history was therefore heavily Eurocentric; like a typical

gringo, the only Latin American artist I could cite with any certainty was Frida Kahlo, who wasn't even from South America anyway.

Following on from this, it seems there have been relatively few exhibitions of historical Brazilian art in the UK. The Ashmolean in Oxford held an exhibition of Brazilian Baroque sculpture in 2001 (titled

Opulence and Devotion: Brazilian Baroque Art). Last year, Tate Modern staged

a retrospective of Hélio Oticica (1937-80), a twentieth-century artist who was integral to the 1960s Brazilian art movement known as Tropicália – not a pre-1900 figure, but still of great importance to the culture of Brazil. So UK audiences aren't accustomed to seeing works from Brazil even in temporary exhibitions.

Solutions

So, what can be done?

Obviously, learning Portuguese would help, in order to engage with both primary and secondary sources.

The most obvious solution to actually

see things is to visit Brazil and spend time in its museums. In some ways, this is a unique situation for Europeans studying the history of Western art (Brazil is part of Western society after all): that, in order to see firsthand examples of artworks from a particular country, you must travel

to that country. Generally, the same problem does not face admirers of art from Italy, or France, or the Netherlands, or Spain, for example, because works produced by these 'schools' or nations have been actively collected in the UK over the centuries and are easily available in museums across the country.

This in turn raises questions about the importance we place on seeing works of art 'in person' in the first place. Can we only 'know' a painting by examining the physical object instead of a reproduction? Thanks to the Internet, I can look at paintings from Brazil online in high quality – the collection of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, for example, has been made partially available by

Google Arts & Culture. So why bother taking an expensive, twelve-hour flight all the way to the country of origin? Generally I don't follow Walter Benjamin's opinion that the reproduction of an artwork devalues the unique 'aura' of that work which can only be appreciated via in-person viewing – I believe the more museums open up their collections online for everyone to access, the better. However, I feel that in this case, given the lack of 'originals' to go by at all, having a real-world point of reference is crucial. If I have never had the experience of examining a painting by a Brazilian artist up-close in its own museum context, in São Paulo or Rio, how am I to really get an idea of its size, colour scheme, subtlety and draughtsmanship – among other visual qualities?

And frankly, looking at a painting on a laptop screen in rainy England means I can't go and enjoy a plate of rice, beans, farofa and fried manioc afterwards, or tea and carrot cake in Confeitaria Colombo as below:

|

| The mirror-lined, Art Nouveau interior of Confeitaria Colombo in Rio de Janeiro, founded in 1894. Own photo. |

Visiting Brazil is not something that can be done easily, though: you need time and funds. During my PhD I allocated myself enough money and time off (my longest trip to Brazil was three weeks) to go and spend time with Felipe and explore more of the country with him. This is something I cannot do in my present situation, although there are options on the horizon which I can work towards.

Another solution which proclaims itself noisily to me is that I should start researching and writing a book on historical Brazilian art for English-speaking audiences – hang on, I'm getting ahead of myself.

Why Brazilian art?

Now for a personal perspective. My complete lack of exposure to Brazilian art at university meant that I only encountered it relatively recently: in 2017, to be exact, when I met Felipe, my boyfriend, who is Brazilian. (Should I cite the

Guardian article that was written about us last year in a footnote for context, or is that too self-indulgent/meta? Probably.) Felipe is a fellow art historian, which helps when it comes to museum-going and sharing insights.

My first visit to Brazil in May 2018 was an excellent introduction to Brazilian art. Felipe and I visited museums in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, as well as his hometown, Juiz de Fora, where there is a wonderful collection, the Museu Mariano Procópio (sadly barely open at the moment because of lack of funding). Looking at the paintings together, Felipe explained the social, political and historical contexts behind them which I, as a

gringo, simply didn't know. In this case it was necessary for art historical observation to be a shared experience; I couldn't have done it alone.

We also travelled to the highly picturesque colonial towns in Felipe's native state, Minas Gerais, which deserve to be described in posts of their own: Tiradentes and São João del Rei (on a later trip we stayed in Ouro Preto, a place I can't describe without tumbling headlong into flowery hyperbole). These

Mineiro towns introduced me to Brazil's unique twist on the European Baroque style in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as exemplified in the sculptures and architectural designs of Antônio Francisco Lisboa (1730/38-1814), better known by his nickname O Aleijadinho ('The Little Cripple').

|

| Igreja Matriz de Nossa Senhora da Conceição de Antônio Dias, Ouro Preto, Brazil, where Aleijadinho is buried. The façade is newly restored but at the time we visited (December 2018) it was closed to visitors. Own photo. |

|

| Ceiling of the Igreja de São Francisco de Assis, Ouro Preto, Brazil, painted by Manoel da Costa Ataíde (1762-1830). Own photo. |

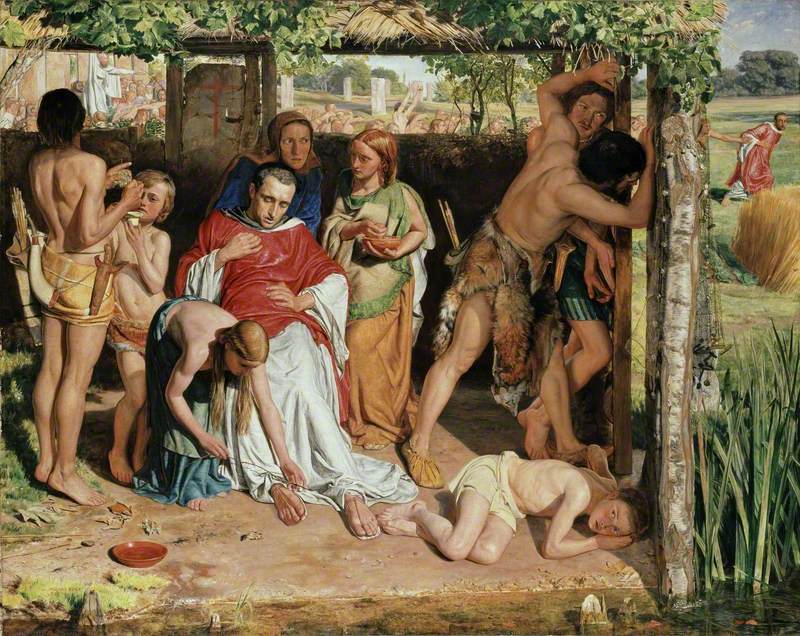

On top of this, I attended a series of presentations given by other doctoral art history students at the University of Juiz de Fora, where Felipe was presenting a paper on his own research (the iconographic representations of the daughters of Louis XV in French eighteenth-century art, FYI). Although the papers were in Portuguese, meaning their content was mostly lost on me, the majority were devoted to nineteenth-century Brazilian artists, so I could still admire the images onscreen. I noted down this intriguing painting by a woman artist, Abigail de Andrade (1864-90/91):

|

| Abigail de Andrade, Um canto do meu ateliê (A corner of my studio), 1884, oil on canvas, private collection |

The point of all this is that Brazilian art has a special significance for me; I associate it with happy memories and positive changes in my personal life. If I hadn't met my boyfriend, I would likely never have encountered Brazilian art or become so interested in it. Perhaps this is something which art historians shy away from acknowledging as a motivating factor in their work: that the academic study of a subject can develop out of one's personal life. Perhaps that's at the risk of seeming egoistic?

One of the purposes of this blog, then, is to begin navigating this art historical field which is new to me, in my own way and despite my limited resources. I've already thought of content for future posts, so watch this space!